Pentarm Static

Background

The ME 2110 class at Georgia Tech has something of a reputation among current and past ME students. The class, in which we are tasked with building an autonomous robot in a team, and then have those robots compete against each other, is notorious for having an immense time commitment, as teams spend days upon days in the machine shop designing, building, and testing.

In Spring 2022, I participated in this rite of passage, building a robot with two other teammates. In this page, I detail the decisions that went into the design of our robot, named the Pentarm Static.

Competition Overview

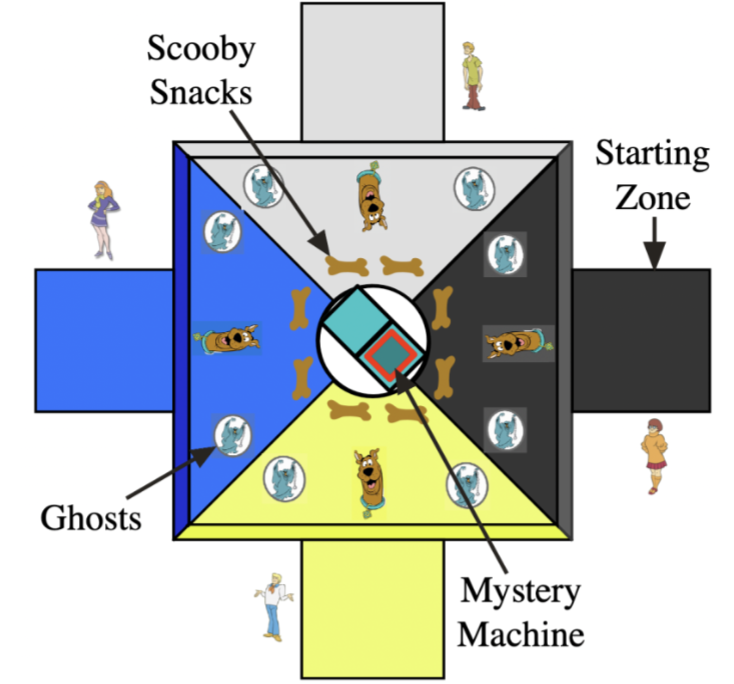

Every semester, the design competition takes the format of a 40 second 4 vs. 4 robot match, in which the competitors attempt to score as many points as possible, by completing various objectives.

The Spring 2022 competition, themed around Scooby-Doo, had the following objectives:

- Chase away ghosts: Near each boundary between zones are 2 kitchen sponges, or "ghosts," approximately in the location of the "Ghost" object in the diagram. At the end of the match, teams lose 1 point for each sponge in their zone, incentivizing them to knock the sponges into other teams' zones.

- Feed Scooby his snacks: Each zone starts out with 2 bone-shaped dog toys, placed where the "Scooby Snacks" are in the diagram. The goal is to move the snacks towards the Scooby decal, with 1 point awarded for each snack moved off of the starting position, 2 points for each snack placed over the Scooby decal, and 4 points for each snack placed over Scooby's mouth on the decal.

- Leave in the Mystery Machine: Each robot is preloaded with an approximately 6-in tall 3D printed model of one of the human characters. The goal is to place the character into the rotating center console with the off-center hole, with 1 point for moving the character outside of the starting zone, 5 points for moving it over or on the center console, and 10 points for placing it inside the hole in the center console.

Every team is supplied with a mechatronics kit, consisting of 2 DC motors, 2 pneumatic pistons, 2 solenoids, 5 mousetraps, and some sensors. These are the only electronics permitted to be used on the robot.

Robot Design

Drivetrain

Due to the small number of actuators allowed, whether or not to have a drivetrain is an important decision, as it influences the actuator allocation and thus design of the other mechanisms of the robot.

We deemed it important for our robot to reach the center console to complete the Mystery Machine task before any other robot, as the first to reach the center could block the hole in the Mystery Machine and prevent the other teams from accomplishing that objective. Since a drivetrain could have at most 1 motor, to preserve enough actuators for the other mechanisms, we felt that it would be too slow to have a robot that drives over to the center console to deposit the character model.

Since it would be faster to move a lighter mechanism rather than a heavier robot, we decided to make a stationary robot that would have mechanisms reaching forward to complete all the tasks. Thus was born the Pentarm Static.

Ghost Chaser Mechanism

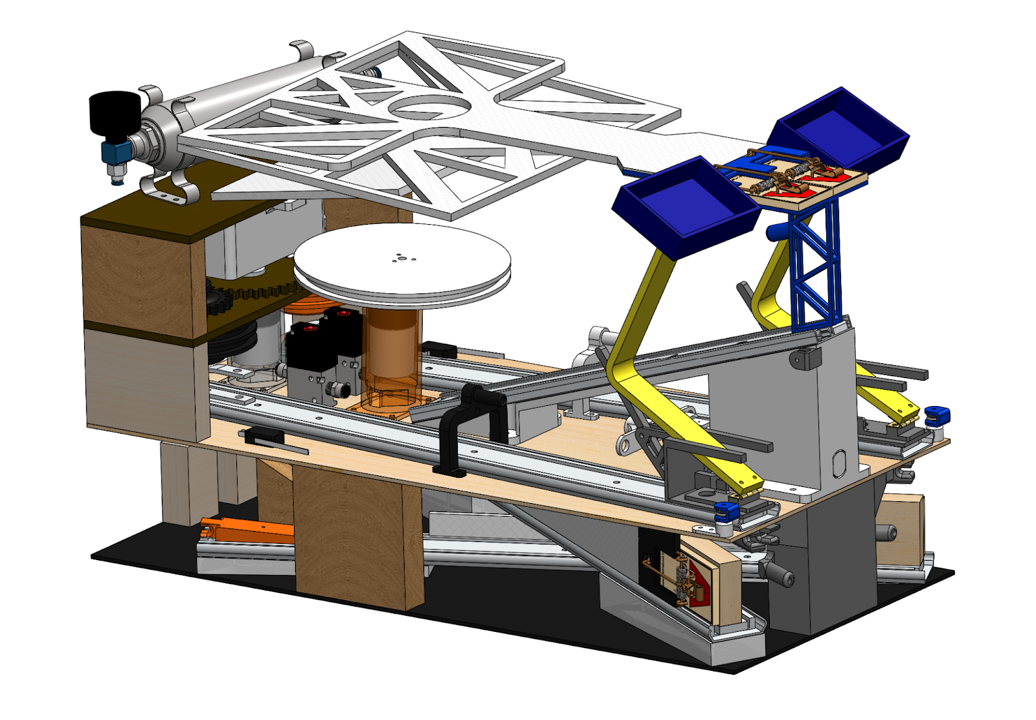

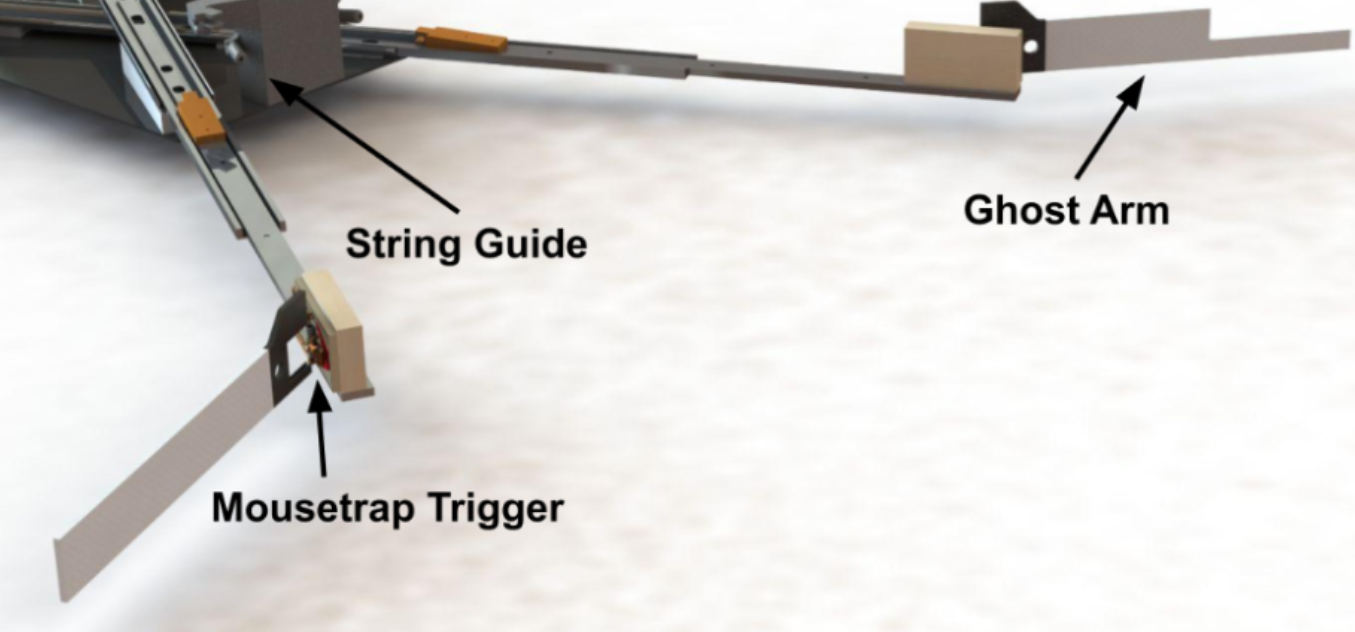

On the bottom layer of the robot are two linear slides that cross each other, right over left. These are part of the mechanism that knocks the ghost sponges into other teams' zones.

The two linear slides are tensioned with rubber bands which go between the rubber hand hook on the back end of the slide and hooks on the string guide part at the front of the robot. The two slides are initially held retracted by a string attached to their backs that goes around pegs at the back of the robot, but once the match starts, a pneumatic piston lifts the string off the pegs, allowing the two slides to shoot out, as the stretched rubber bands return to normal length.

At the end of the linear slides are mousetraps which hold ghost slapping arms retracted. Once the linear slides are at maximum extension, a string connected between the mousetrap trigger and the main body of the robot goes taut, triggering the mousetrap and swinging out the ghost arms, which slap the ghosts over to the neighboring zones.

Scooby Snacks Mechanism

The middle layer of the robot contains the mechanism for gathering the two Scooby Snacks. Probably the most complex mechanism on the robot, it involves 2 actuators, a set of gears, and lots and lots of string.

At the start of the match, the two arms extend out. On each arm, the string connected between the main body and the bottom of the trigger arm goes taut at max extension, rotating the trigger arm and pushing the snack arm down, placing the cups on the end over the Scooby Snack. The arms then retract, and a piston on the main body of the robot pulls some string that rotates the 2 snack arms together. Velcro on the walls of the 2 cups causes them to stick together as the arms retract, stopping over the decal of Scooby-Doo, specifically over his mouth.

The extension and retraction of the linear slides are controlled by a DC motor at the back of the robot, with a system of gears transmitting the power to 2 spools. The system is geared for speed, at about a 1:1.6 gear ratio (actually 23:37), since there is not much opposing force for the motor's rotation, and speed is important for competitive reasons. An encoder on the left gear shaft tracks the movement of the linear slides, ensuring a level of precision in picking up and dropping off the Scooby Snacks.

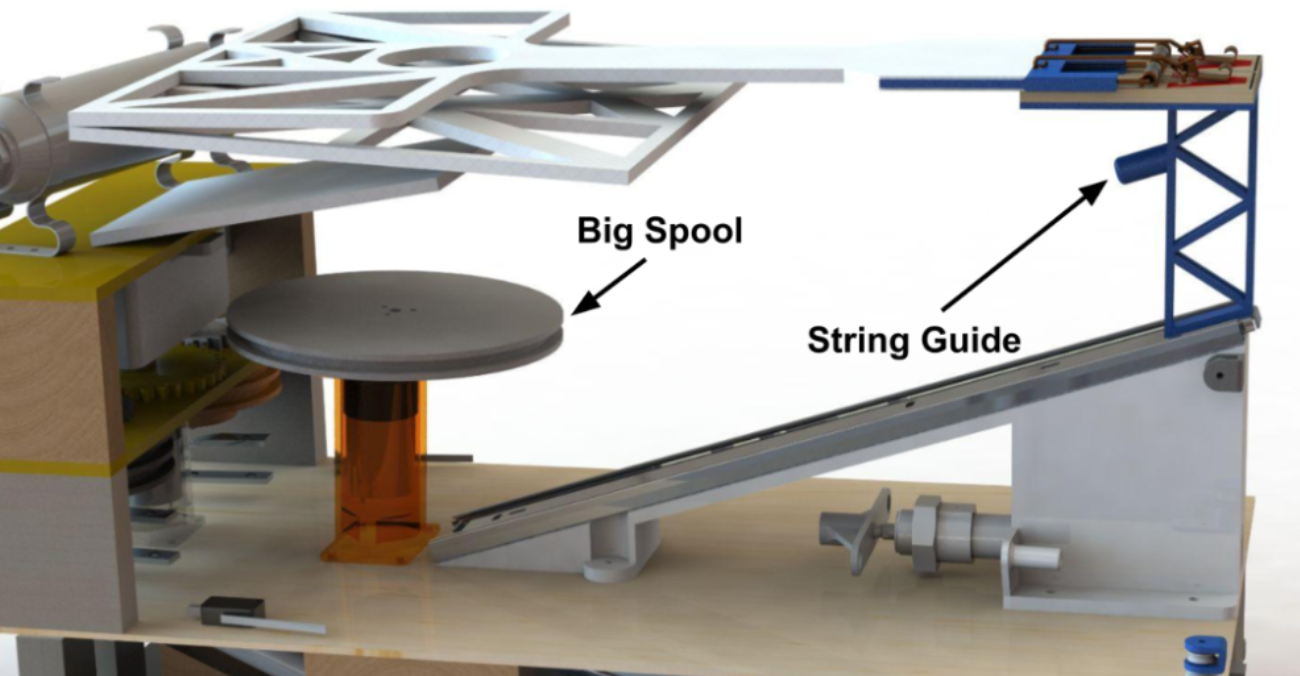

The spools each contain two sections, one to hold string for extending the arm, and the other to hold string for retracting the arm. The extension string goes from the spool, through the bearing pulley at the front of the robot, and then back to the rear end of the slide. Thus when the spool retracts in the extension string, the rear end of the slide is pulled towards the front bearing pulley, thus extending the slide. The retraction string, works in pretty much the opposite manner. Connecting from the front of the slide to the spool, when the string is tightened, it pulls the slide back in. The strings are wound such that tightening the extension string relaxes the retraction string, and vice versa, so that only one is pulling at a given time.

Character Mechanism

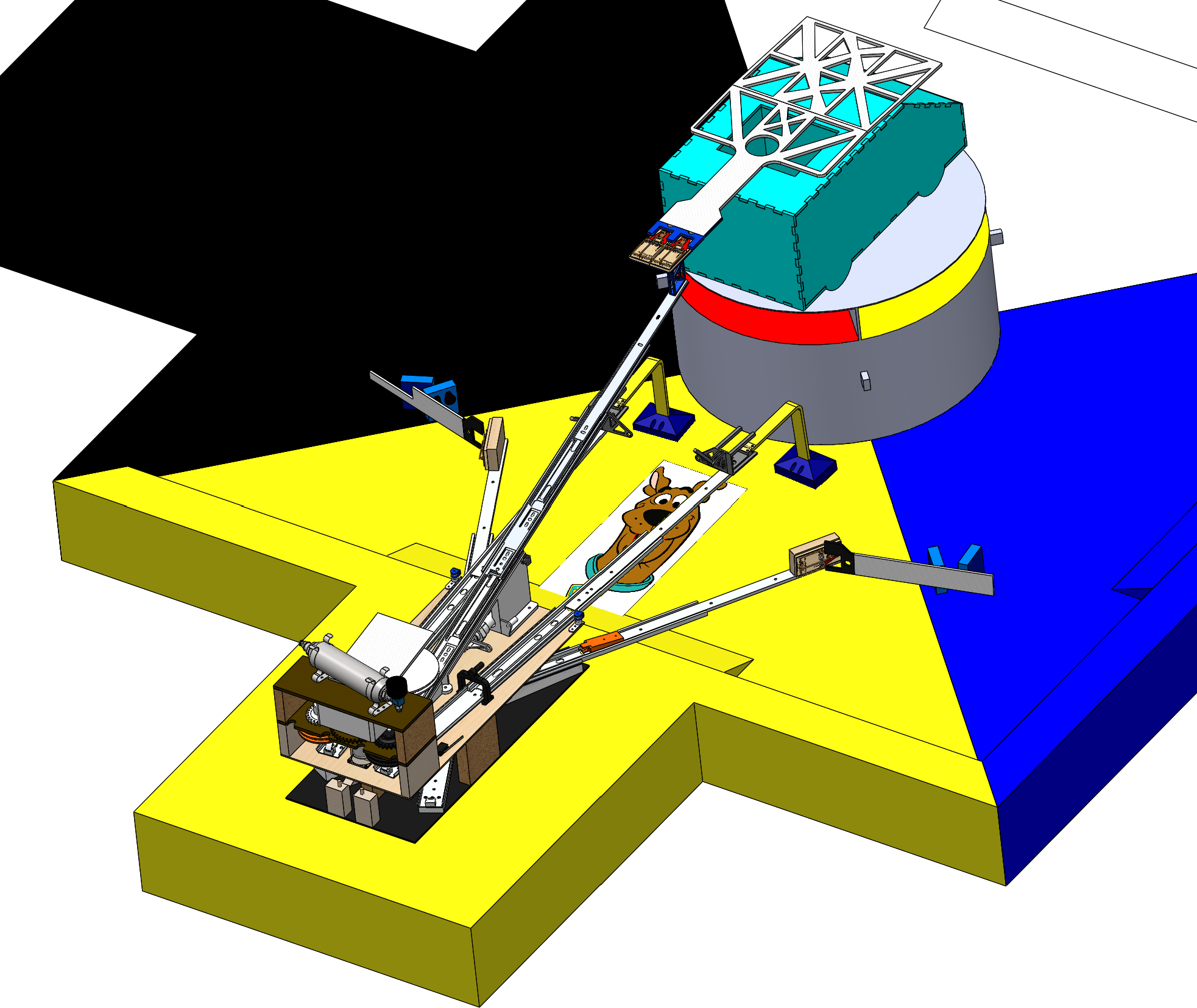

The final mechanism is the one that deposits the character model into the Mystery Machine in the center of the field. As mentioned in the Drivetrain section, we deemed it important to reach the center console before any other robot, and so this mechanism is optimized for speed.

Similar to the Scooby Snacks mechanism, this mechanism also uses strings and pulleys to extend the slides. However, the string spool for this mechanism is a lot larger, about 4 inches in diameter, to increase the speed at which the slides extend. In addition, the stringing uses cascading rigging, which means that all the slide stages extend simultaneously, rather than one at a time, which is how linear slides conventionally extend. We found that this resulted in a speed increase of 2x in our case.

At the end of the slides is the arm that places the character. Similar to the ghost slappers, the arm is held retracted by a pair of mousetraps, but a string connected between the mousetrap trigger and the main robot body goes taut at the maximum extension of the slides, thus flipping the arm. We designed the arm to not require a lid to keep the character in while we wait for the center console to rotate the hole towards us—instead, the arm pins the character model against the roof of the Mystery Machine, until the hole passes underneath, at which point the character model falls in.

The character arm also includes a folding block plate. If our robot was not the first to reach the center console, the block plate would stay folded up, allowing us to still deposit our character without interference. However, if we reached the center console first, the block plate would unfold, blocking the top of the Mystery Machine and preventing other teams from scoring points.

The optimizations for speed resulted in the tradeoff that the mechanism could not move much weight. As a result, we needed to design the mechanism to weigh very little. The character plate and block plate were made from corrugated plastic, which we found to be a lightweight yet strong material. We also cut weight-saving pockets into the block plate, being conscious to not make the holes too big such that other teams' characters could pass through. This allowed us to use mousetraps instead of a pneumatic piston for actuating the mechanism, further reducing the weight.

Results

In the final competition, the team made it past the preliminary rounds, losing in the first elimination round, which is a respectable finish. However, we were all very disappointed with the performance of Pentarm Static. This video is of our elimination round match, and it shows all of the mechanisms failing to work properly. The snack arms are not able to hang on to the Scooby Snacks, the ghost slappers fail to deploy, and the character mechanism does not move at all.

We believe that the reason our robot did not perform well was because of its complex design. We spent a lot of time fixing issues that would arise from the mechanisms, which left us with inadequate time to stress test the robot. As a result, the robot failed in unexpected ways.

A key lesson we learned was to keep designs simple. The winning robot used a lot of the same ideas that we did, like not using a drivetrain, and using linear slides. But they had simpler mechanisms, such as sweeping the Scooby Snacks using arms, rather than using string-controlled cups that had to land exactly on top of the snacks. This meant that they had more time to test their robot, and find any potential issues to fix beforehand.